Gaining a competitive edge

25 April 2008

More Industrialised construction methods produce buildings using significantly fewer resources, in terms of labour and materials, according to new report by UK building economists Bernard Williams Associates (BWA). Such techniques are commonly used in some parts of Europe but the report suggests that wider adoption of these methods could raise competitiveness in Europe's construction industry.

The report is the first of four studies looking at benchmarking the competitiveness of Europe's national construction industries, funded by the European Commission. The Commission awarded the contracts as part of its drive to revitalise Europe's Lisbon Agenda (see FIEC feature in CE Sept 2005) on sustainability.

The BWA report is the first to be published and investigated resource usage and competitiveness in EU construction industries. The study also looked at impact of national framework conditions.

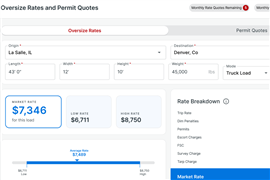

BWA's research team analysed the project costs of over 80 building types in 12 countries and also developed a database of earlier reports on the same subject. Using this information, along with interviews with construction experts from across the EU, BWA developed a prototype benchmarking system.

The system links the actual cost efficiency levels as calculated in the project cost analyses with the observed efficiency of the processes used in each country. The model compares the use of labour resources- the number of on and off site workers - between the countries in the study and shows how well the resources are managed.

According to FIEC, one of the most significant findings of the report was the relationship between use of industrialised construction methods - commonly used in Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany and Nordic countries - and the use of fewer resources.

Poor Performers

The report also found the countries, including the UK, Ireland, Spain, France and Italy, which have failed to move forward from the traditional consultant driven process make less efficient use of resources. BWA claims that these conditions give contractors little opportunity to innovate and optimise the technical design to make resource savings.

FIEC believes that the other interesting finding of the report is that the rates of pay for construction workers tend to be higher where construction methods are more industrialised. However, because these workers are better trained and motivated, they need less supervision. Also, the use of industrialised methods of working are significantly faster, so although on site pay rates are higher, the overall cost of labour measured across the whole production process is generally rather less.

In the most extreme case, the study reveals that office buildings per square metre in the UK now cost almost double what a similar building costs in Belgium, while the cost of labour in Belgium is almost twice that prevailing in the UK. This comparison reveals an astronomical difference in relative efficiencies.

During the research phase of the study, BWA noted that Belgium is the only country that has developed its own voluntary hybrid form of decennial defects liability insurance. The system does not give any right for court action for negligence against the 'guilty' party in the event of a claim for defective design or workmanship during the contractual defects liability period.

The report claims that while the effect of such 'project insurance' policies for clients is to drive up the quality of construction, they allow contractors to innovate and drive down the use of resources. However, the removal of subrogation rights promotes a genuinely integrated team and avoids the potential for wasting resources on negligence claims against the 'guilty' party.

Wider View

BWA's final conclusion is that less efficient countries would do better to benchmark their performance against the best performers in Europe, rather than their national peer groups. However, it adds that benchmarking is purely a diagnostic tool that measures performance but cannot explain the differences it reveals.

The report states that diagnosis and identifying the weak links in the construction process is only the start of the process. Instigating the necessary change is more challenging and something each member state must tackle individually.

FIEC has also analysed the results of the study and suggests that what is needed for an efficient construction process can be summarised as follows;

• Extensive industrialisation of the construction process;

• Total or partial delegation of detailed design to the contractor;

• A well-paid, well-trained, industrious workforce;

• Limited sub-contracting;

• Well developed lean construction management;

• Total project insurance to facilitate integration of the design and construction.

Extracts from the report, as well as graphs and graphic demonstrating the relative efficiencies of various construction processes is available at www.bwassoc.co.uk/euconstructionefficiency/. The report is in English with an executive summary also available in French and German.