How are materials passports changing construction?

08 June 2022

Materials passports, digital documents containing information on all the parts of a building, are frequently used in parts of Europe and the concept is gaining traction all around the world. Lucy Barnard speaks to Pablo van den Bosch, director of Madaster, one of the world’s biggest materials databases, to find out more.

For Woonstad Rotterdam it all started with toilets.

In 2018, the Dutch housing corporation which manages around 60,000 homes and offices needed to install bathrooms into a block of new social homes it was building in Rotterdam.

Rather than purchasing the loos new from a building merchant as it would have done ordinarily, Woonstad’s management decided to follow through with Rotterdam’s recently adopted Circular Economy strategy and put in a bid to buy them from the nearby Erasmus Medical Centre which was demolishing some of its buildings and had registered their materials in an innovative new ‘materials passport’ computer file.

Pablo van den Bosch, director at Madaster, one of the largest materials passport firms in the world. Photo: Madaster

Pablo van den Bosch, director at Madaster, one of the largest materials passport firms in the world. Photo: Madaster

“The hospital registered the buildings that were going to be demolished. And instead of inviting demolition contractors onsite, they invited multiple parties to look at the data that they had registered and asked for solutions to maximise the revenue and reuse potential of these products and materials,” says Pablo van den Bosch, director of Madaster, the materials passports firm running the project.

Eventually Woonstad’s low bid was accepted, and the firm also managed to acquire ceiling plates, doors, wooden beams, steel pipes and plasterboard – all at knock down prices – which were loaded onto trucks and driven across the city direct to the housing site once the hospital buildings were demolished.

“In the end everyone was pretty happy,” says van den Bosch. “The demolition took place close to where the materials were taken so the transportation was a lot more efficient. The extra effect was that the materials for landfill or incineration decreased, and the social housing corporation was pretty happy with the stuff that they got in the end for as good as nothing.”

Materials passports, digital documents containing information on all the parts of a building, are frequently used in parts of Europe and the concept is gaining traction all around the world.

In the Netherlands, where the idea is arguably most advanced, the Dutch government has introduced tax incentives for developers who register material passports, and it is considering making them mandatory for new buildings. Earlier this year the Netherlands increased its Environmental Investment Rebate Scheme (MIA), a tool allowing commercial real estate owners to get a tax advantage of up to 45% on their investment in cicular construction.

In April 2021, Madaster signed a partnership with UK-based engineering and design firm Arup to support the platform as it expands its network. And the portal has already signed similar agreements with construction firms including Interboden, Drees & Sommer and Commerz Real.

How do materials passports work?

First created as a prototype by the EU-sponsored Buildings as Materials Banks (BAMB) programme which started in 2015, the idea is to make it easier for construction firms to incorporate as many materials as possible from old buildings rather than buying new ones.

They do that by creating a detailed digital record of what exactly is in the current building stock. That way, anyone looking for new building materials can find out what materials are likely to become available and put in an offer for them.

The idea has widespread implications for the way buildings around the world are constructed, maintained, demolished and – hopefully rebuilt.

According to European Commission data, buildings in the EU are collectively responsible for 40% of energy consumption and 36% of greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, they account for half of all new material resources and generate more than a third of waste across the bloc.

Buildings in the EU account for half of all new material resources and generate more than a third of waste across the bloc. Photo: Adobe Stock

Buildings in the EU account for half of all new material resources and generate more than a third of waste across the bloc. Photo: Adobe Stock

“Circularity is very simple. If you know how to make something, you also know how to remake something,” says van den Bosch. “If you are a carpenter, you know that you can use the same piece of wood two times. You just take out the nail and reuse it again. In this circular world materials are key. And if you make something, if you are linked to a building, instead of throwing away the information, keep it.”

Of course, the concept is not a million miles away from current practice where most demolition contractors bring anything salvageable to their yards to sell. But van den Bosch points out that by bringing the process online there can be huge savings in terms of costs, carbon and time.

“One of the challenges with the current system is that the actual materials and products are only seen and identified when the demolition is taking place,” he says. “So, you need to move to a yard because you need to store it and transport all the materials there. How nice would it be if you could do the same thing but digitally and not when the actual demolition is taking place but three years in advance so that when you do the demolition you can directly transport products and materials to the new destination? That saves a lot of transportation costs and a lot of space. A digital process makes it a lot more efficient and therefore hopefully cheaper and better for the environment.”

Although a number of firms around the world are currently offering to create materials passports for clients, only a handful, including Dutch-based Madaster and German-based Building Material Scout, have so far managed to create commercially viable platforms at any scale.

Key product and material information

Madaster says it is fully operational in five countries - Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium and Norway – and is currently looking to establish an offering in the UK. The company has also registered projects located in the UK, Spain, Finland, Denmark, Australia, Taiwan and Luxembourg.

After paying an annual subscription of between €200 and €2,000 a year, Madaster subscribers are able to create a document for any building and then upload specific BIM data onto the site. Currently anyone involved in the construction is able to register the materials passport with Madaster but van den Bosch says that ultimately the building owner is considered the owner of the document and therefore able to grant access to its data to anyone in the construction team with data to contribute. When the building is due to be fully or partially demolished, the building owner is able to make information about the materials accessible to the public.

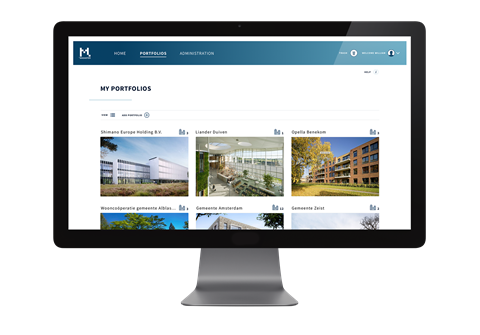

Madaster has registered projects in the UK, Spain, Finland, Denmark, Australia, Taiwan and Luxembourg. Photo: Madaster

Madaster has registered projects in the UK, Spain, Finland, Denmark, Australia, Taiwan and Luxembourg. Photo: Madaster

“In theory, if you are a product manufacturer and you are going to deliver concrete blocks to the construction site, you can request access to the passport to download environmental information about the concrete blocks at the same time,” he says.

“In practice, what we see is that a lot of this is done automatically. We have connections to many data sources that contribute information about products and materials. We upload the design, the BIM model, we recognise what type of products and materials are included in the design and we enrich the data with environmental and circular information about these products and materials.”

The platform then generates the passport, drawing on information from other sources of product and market data when it can. Madaster says that by detailing all of this information online it not only makes it easier for construction workers to change or deconstruct a building, but it can also increase its value by putting a clear figure on how much each of the ingredients is worth.

“If we have the appropriate data we can do all sorts of things,” says van den Bosch. “When a designer sketches a wall on paper, he may only say that it is made from a type of stone and then we cannot calculate it accurately. We need to know the design and the materials. For instance, if it is made from concrete and the manufacturer created a special concrete mix that has a very positive carbon footprint then we need to have that data to upload the specific information. Then we can calculate carbon or cost at the press of a button.”

Each account is only accessible to view if the building owner grants permission. However, from July, Madaster says it plans to start granting public access to anonymised information on an area level so that users will be able to see the types and quantities of materials used on a city or neighbourhood level.

Reusable construction materials

“This information could be used for policymaking. For instance, if you are a municipality and you want to redevelop a particular area, you can look at what type of materials are available in the area and which ones can be reused,” says van den Bosch.

Moreover, van den Bosch hopes that, as the system takes off, owners will start to use the information in it to sell off materials as and when they become obsolete.

“Madaster is not a marketplace. You cannot buy stuff. We are not a shop. We are just a register. But if you want to set up a marketplace and you would like to have the data in our database. As you can imagine it’s the present owner that needs to approve that but on an area level we can exchange that data to marketplaces,” he says. “We want to facilitate views of the data that we have in order to stimulate new business models that are set up around reusable construction materials.”

To that end, Madaster includes any known history of the various materials included in each property as well as estimates on what materials are likely to become available for reuse in the future and when they are likely to become available. The company hopes that bringing the information on the fabric of a building together in an easily accessible manner can act as a sort of ‘health check’ for owners, indicating at the touch of a button whether steel joists or wood panels have had structural issues or a lifetime of heavy wear and tear.

Assessing construction material availability

“We know that the average lifetime of a building is somewhere like 60 years,” says van den Bosch. That’s a generic assumption. But within that we can get a bit more specific. We know that materials used for insulation on average become available after 15 – 20 years. So, we can give estimates on when will what materials become available.”

Although he believes that buildings with materials passports will ultimately become more desirable to buyers than those without them, van den Bosch says that, at the moment it is real estate developers in the Netherlands which are finding more commercial use for the documents as a way of winning favour with local councils.

“We think that real estate is something fixed for the next 50 years but that’s a lie. It’s not reality. Buildings change all the time. So, if you work in an office, the way we use meeting rooms is changing,” he adds. “In five years’ time we go from open spaces to smaller cabins to meeting rooms to individual rooms. Then we get a new tenant. They want to do an adjustment because they want it to look nicer. Buildings are always in transition. And we forget that a lot. But there is a continuous flow of materials coming in and out of buildings.”