Material concerns: What the global energy crisis means for construction

12 April 2022

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is sending already stretched costs of steel and concrete soaring. Lucy Barnard finds out how the construction industry is one of the most exposed to the global energy crisis and how super high gas bills are impacting projects

In the German city of Stuttgart cost overruns are a sore point. Work on the Stuttgart 21 megaproject to redevelop the city’s historic railway terminus and reconfigure it as a cutting-edge underground transport hub is already three years late and more than three times over budget.

Reasons for the drastically slipping timetable for the project – named because it was supposed to ring in the 21st century – include anything from planning delays to new environmental regulations designed to protect biodiversity.

The famous Mercedes sign on top of Stuttgart’s historic Paul Bonatz Hauptbahnhof is removed as part of Stuttgart 21. The megaproject is one of many to have been hit by the spiralling cost of building materials as a result of the global energy crisis. Photo: Reuters.

The famous Mercedes sign on top of Stuttgart’s historic Paul Bonatz Hauptbahnhof is removed as part of Stuttgart 21. The megaproject is one of many to have been hit by the spiralling cost of building materials as a result of the global energy crisis. Photo: Reuters.

But in March, when German state railway company Deutsche Bahn, which jointly owns the project alongside the federal, city and state governments, announced that it was again revising the budget to assume total costs of €9.15 billion (US$9.9 billion) the reason it gave for adding an extra €950 million (US$1.03 billion) of costs was the rapid increase in the price of construction materials.

“The reason for the unfavourable development is considerable price increases for construction companies, suppliers and raw materials,” a Deutsche Bahn spokesman said in a statement published after a meeting with the project supervisory board which oversees the scheme and which had determined a previous cost framework of €8.2 billion (US$8.9 billion) in 2018.

Deutsche Bahn is not alone. Construction firms across the world are worried that their heavy use of materials manufactured using energy-intensive processes is pushing up costs and leaving them particularly exposed to the global energy shortage.

In March, gas prices surged to crisis levels as Western sanctions introduced in retaliation to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine bit hard into supply already stretched by a global rebound in demand following the pandemic.

According to Reuters, prices for wholesale natural gas have surged to record levels, reaching more than €120 (US$130.6) per megawatt hour at the start of April, up from €19.2 (US$20.9) a year earlier. Oil prices have also risen sharply since the pandemic, with the price of Brent crude rocketing from a low of US$24.64 a barrel in April 2020 to $105.25 a barrel in April 2022. And futures for thermal coal – the sort used in power stations – soared to US$281 a tonne in April 2022, up from US$49.28 in 2020.

Rising energy prices

“Energy costs make up approximately 30% of the construction materials costs,” says Agnieszka Krzyzaniak, global research manager at Netherlands-headquartered design and engineering firm Arcadis, speaking to International Construction. “With energy prices doubling or tripling in recent months, this will easily lead to double digit percentage price increases for the materials.

“In Q2 and Q3 of 2021 inflation was being driven mainly due to the very high prices of raw materials such as iron ore, copper or timber. Then in Q4 rising energy costs kicked in. As such, not only did the costs of products such as steel kept increasing, but also they were joined by other energy-intense products such as glass, bricks or roof tiles.”

Russia is the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, accounting for around 45% of the European Union’s imports in 2021. It is the third largest oil and the third largest exporter of coal.

Although the sanctions imposed by Western governments on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine do not include natural resources, most Western trading partners have stopped doing business with the country. Instead, they are trying to make up for the shortfall by searching for alternative suppliers from other countries, increasing demand in a market when supply was already limited due to the rebound following the pandemic.

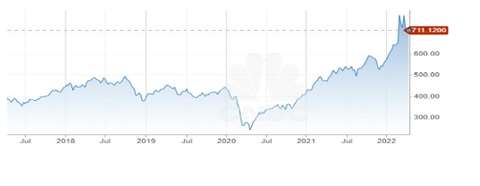

S&P’s GSCI index which tracks global raw materials prices rose to its highest level in a decade this year. Source: S&P data via CNBC

S&P’s GSCI index which tracks global raw materials prices rose to its highest level in a decade this year. Source: S&P data via CNBC

The impact on global commodity prices has been dramatic. The S&P GSCI index which tracks global raw materials prices for commodities including industrial metals and energy, jumped from 1,002 at the start of January to 3,748.

“We have already seen a 25% increase in structural steel costs and a 50% increase in rebar,” Krzyzaniak says. “It is very likely that further cost increases will follow as a result of increasing energy costs.”

Maurice van Sante, principal economist for construction at Amsterdam-headquartered ING Research, tells ICON that although contractors themselves use very little natural gas, the building materials industry one of the most energy intensive sectors after aviation, shipping and the chemicals industry.

“A lot of energy is needed for the production of bricks, cement and concrete,” he says. “Many building materials firms use a large amount of gas in their energy mix compared to other energy-intensive sectors. This makes the sector particularly vulnerable to an interruption of Russian gas supply.”

Steel prices are some of the hardest hit, partly due to the fact that Russia is the world’s fifth biggest steel producer while Ukraine is the fourteenth.

In February Europe’s largest steel maker, ArcelorMittal, said it would reduce operations at its Kryvyi Rih steel plant in Ukraine to a “technical minimum” following the Russian invasion. A month later it increased its official hot rolled coil offer (HRC) by €180 (US$195) per tonne.

Why are steel prices increasing?

At the same time, British Steel wrote to customers informing them that it was increasing prices for all new orders of structural sections “with immediate effect,” by £250 (US$325) per tonne, an unprecedented increase estimated to amount to around 25% and the latest in a series of price increases the company levied throughout 2021.

“Due to the crisis between Russia and Ukraine, we have seen extraordinary levels of volatility in commodity and energy prices as well as a significant disruption to international trade flows,” British Steel wrote, noting that electricity prices were around eight times higher than the 2019 average, natural gas prices were at “unprecedented levels” and the cost of raw materials such as metallurgical coal were at an “unprecedented high.”

It is a similar story elsewhere with steel futures prices rising to levels not seen in a decade. Spot prices for Northwest European hot rolled coil (HRC) jumping nearly 40% in March while prices in North America and China increased by around 7-8%.

Cement and brick manufacturers too are being forced to hike prices as they struggle to swallow record energy bills.

Van Sante estimates that these manufacturers need to use around 8.3 terrojoules of natural gas in order to produce €1 million of value-added output, far higher than metals manufacturers which need around 7.2 terrojoules of natural gas for the same outcome and contractors which use just 0.1.

Cement manufacturers raise prices

Although the cement industry usually revises its contracts on a yearly basis, in February Switzerland-based cement manufacturer Holcim said that it would raise prices several times in 2022 to pass on soaring outlays on energy supply for a second year in a row.

Holcim told ICON that, although it could not comment on sequential price increases, it was pursuing, “a number of strategies to mitigate the increase in power or electricity prices, including pricing and cost control measures to contain such inflation effects.”

It’s a similar story at brick manufacturers too with Austria based Weinerberger, the largest brick maker in the world, and UK-based Forterra and Michelmersh all putting up prices by around a tenth in recent months.

Wienerberger, the world’s largest brick manufacturer, has increased prices in response to rising energy costs. Photo: Wienerberger

Wienerberger, the world’s largest brick manufacturer, has increased prices in response to rising energy costs. Photo: Wienerberger

Although Weinerberger said that, like many major energy users, it had bought around 90% of its gas for 2022 in advance, the company’s chief executive Heimo Scheuch reported that many of its smaller rivals had been forced to shut down operations over the winter months leading to an undersupply, that was again pushing up costs.

Van Sante says that, although they are more energy intensive, manufacturers of materials such as concrete cement and bricks, have been slower to pass on increased energy costs to customers.

“For steel and timber, there is a global market with a huge number of buyers and sellers. This makes these markets competitive and transparent and this results in a more direct pass-through in the value chain of price changes of raw materials,” he says.

“Conversely, the markets for concrete, cement and bricks are more local. This is due to the characteristics of these materials. They are large and heavy and therefore difficult and costly to transport. This makes these markets less competitive with higher profit margins and are a cushion for higher procurement prices. The pass-through of procurement price fluctuations is therefore slower.”

So, will contractors be able to pass these costs on to customers or could they be forced to absorb some of the impact themselves?

Certainly, according to the European Commission construction survey, an overwhelming number of contractors are planning to hike tender prices over the next three months. It found that a net balance of 45% of contractors surveyed in March reported that they expected to increase output prices – the highest number recorded since the start of the century.

How much have building costs increased?

UK headquartered Mace Group is forecasting that contractors will increase tender prices by 5.5% in 2022 after a record jump of 7.5% in 2021, primarily driven by rising materials costs. “Construction orders look strong as we go through the first quarter of 2022 however this growth is likely to be tempered by geopolitical factors driving rising oil and gas prices,” says Matt Fitzgerald, commercial director at Mace Cost Consultancy.

And what about projects which are already under construction? Back in southern Germany, the increase in costs of the building materials being used in Stuttgart 21 are being met by the public purse.

Krzyzaniak says that whether this will be the case for other projects hit by spiralling materials costs is “very difficult to quantify.”

“It depends whether contractors and their suppliers have negotiated fixed prices for their contracts,” she says. “We can only say that contractors operating in industrial or residential markets are likely to be able to pass on most of the costs – but it still leaves them with the challenge of actually securing the materials and shielding from delays.

“The situation is more challenging for the ones working on public works, especially multi-year contracts agreed pre-pandemic and on fixed prices. We are seeing more evidence of inflation risk-sharing by clients and contractors as a means of sharing the pain and protecting the solvency of the contractor supply chain.”