Why the pandemic is encouraging more women to work in demolition

04 January 2022

The global pandemic is changing the working patterns of millions of people across the globe. Holly Price, a director at Keltbray, tells Lucy Barnard why it is also encouraging more women into the ‘macho’ demolition sector - and the construction industry in general.

Holly Price, a director at British demolition firm Keltbray, struggles to remember her working life before the pandemic.

“I don’t know how I managed to physically get to so many meetings and to travel so much,” says the director of skills and communities, an explosives engineer by training who, until recently, also acted as president of the National Federation of Demolition Contractors.

“The pandemic has showed us all that we can use technology like Zoom and Teams and I think that has been really beneficial for my work-life balance,” Holly Price, Keltbray

“The pandemic has showed us all that we can use technology like Zoom and Teams and I think that has been really beneficial for my work-life balance,” Holly Price, Keltbray

“The pandemic has showed us all that we can use technology like Zoom and Teams and I think that has been really beneficial for my work-life balance,” she says. “Now, if I can get online, I can work.”

Price, who started her career in the demolition sector aged 17, trained as an engineer and worked her way up to become the first female explosives expert in Europe in the sector, also works to promote diversity and attract newcomers of all backgrounds to the sector which is typically seen to have one of the most macho cultures in construction.

“I would argue that the pandemic is a golden opportunity to re-balance the construction industry as a whole,” Price says. “In the past construction companies have not always approached jobs with flexibility in mind. We haven’t questioned whether it is necessary to have every member of a team on site for ten hours a day. Covid has proved that some people can work remotely.”

Although she stresses that it is still too early to really know what the full effects of the pandemic have been on everyday life and that many demolition jobs by their very nature must be performed on site, Price says that the restrictions forced on firms could provide a very much needed kick to help the industry attract and retain more women.

How to improve diversity in the demolition sector

“If you had asked about flexible working two years ago, I think most employers wouldn’t have understood what you were talking about and if they did, they would have said absolutely not,” she says. “Presenteeism has been a big problem in the construction industry.”

“Things were beginning to change before covid, but the pandemic has meant that people are more open to opportunities in the sector,” says Price.

Price’s view seems at odds with the situation at the beginning of the pandemic where more women than men dropped out of the workforce in order to buffer a sudden loss of childcare and shoulder the burdens of home schooling, which created what some economists have dubbed a “she-cession.”

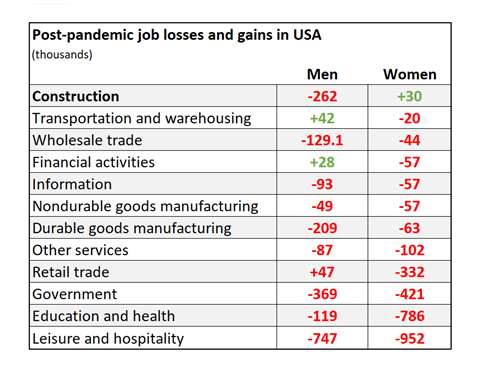

And add to that the fact that unlike the “man-cessions” of the 1970s which affected heavy industries such as construction and manufacturing, the sectors most affected by successive lockdowns have happened to be the service sector – restaurants, retail, childcare and education – where over half of employees are female.

Credit: BLS Data.

Credit: BLS Data.

Yet, figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and analysed by thinktank Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), show that although women in the US made a collective net loss of more than 3 million jobs between February 2020 and September 2021, the construction sector was one of the very few industries where the number of jobs held by women over that period actually increased by 300,000.

“This current trend is genuinely new,” says Ariane Hegewisch who leads the Employment & Earnings programme at the IWPR. “In previous downturns women lost more jobs than men in the sector but this time women actually increased their share of jobs.”

Certainly, the need for more women to enter and remain in the demolition and construction industries across the developed world is painfully clear. Before the pandemic, McKinsey estimated that women make up just 12% of the global construction industry – around 8% in the EU, 10% in the US, 11% in the UK, 12% in Australia and 13% in Canada.

“Construction jobs tend to be well-paid when compared with other work that does not need a college degree, so for many years, entry-ways into the trades have been tightly guarded,” says Hegewisch.

How the pandemic can boost diversity in demolition

She believes that the post-pandemic boom in construction, coupled with a chronic shortage of skilled workers could act as a catalyst to make the industry more diverse.

She points out that during the pandemic most countries and states not only treated construction – and demolition - as an essential service which was allowed to continue during lockdowns, but governments have also invested heavily in construction and infrastructure projects as part of a plan to kick-start the economy and create more jobs.

Although construction workforces fell slightly at the start of the pandemic, state capital investment projects coupled with a housing boom prompted by a shift in preference to larger homes in towns and suburbs, led to a swift recovery which triggered a rapid increase in vacancies. In the States alone, Joe Biden has signed a US$1.2trn infrastructure bill which could create thousands of jobs.

In the past, younger workers tended to bear the brunt of job cuts during recessions while older managers were often the ones keeping their jobs. But, says Hegewisch, the aging demographic of the construction sector, this time around has meant that when the pandemic hit, a significant number of the baby boomer generation saw it as a natural segue to early retirement.

Certainly, in many developed countries, the construction industry has struggled to recruit and retain staff since the 1970s and 1980s. According to US government figures, in 2018, around 22% of construction workers were aged 55 and over – up from just under 17% in 2011. UK statistics paint a similar picture, with the 2011 census estimating that one in every five UK-born construction workers was aged over 55.

“Even before the pandemic, the US economy was booming which meant that white men who might otherwise have gone into construction could go elsewhere and get better paid, less strenuous jobs. So in some areas of the US, we have seen more women recruited into the trades,” Hegewisch says.

Yet, even when more women are succeeding in breaking in to the construction and demolition sectors, numbers published by large construction businesses continually show that the average woman in the construction industry is paid up to a third less than her male colleagues.

UK law firm Pinsent Masons, analysed the gender pay gap reports published by 118 construction employers in the UK during the year 2020-21. It calculates that on average, contractors paid the men they employed around 20% more than the women. Men also received an average of 20% more in bonus payments during the year compared with their female colleagues.

Price’s firm, Keltbray, for example, reports that its female employees on average receive around a quarter less in pay than their male counterparts – something the company puts down to the high number of women in part time and administrative roles and low numbers of women employed in senior management roles. Other major contractors around the world report similarly stark figures with the UK’s Mace reporting a gender pay gap of around a third, ACS in Spain reporting a pay gap of 26.7% and Hochtief in Germany reporting a pay gap of between 11.2% and 15.9%.

Unlike IWPR’s Hegewisch, who is concerned that by encouraging women into specific “green” construction jobs, the industry risks creating silos, trapping them in lower-wage sectors and restricting job prospects in future, Price sees new opportunities for women in so-called ‘green construction’ roles such as environmental engineers or sustainability consultants.

These are often less site-based than other construction roles and allow more flexibility. “There are lots more opportunities for women in the construction sector than there were because there are more expectations on contractors,” she says. “The whole scope of what we do has changed. This new work is creating new opportunities and some of these are attracting women. We’ve been recruiting for net zero sustainability roles and women have been drawn to these roles.”

| Company | Gender Pay Gap 2020-21 |

| ACS, Spain | 26.7% (female senior management and university graduates earned an average salary of just €56,726 while their male counterparts earned on average €77,384) |

| Hotchief, Germany | 11.5% for executives, 11.2% for managers, and 15.9% for those at a non-manager level |

| Mace, UK | 31.2% mean gender pay gap; 36.4% median pay gap. The Group’s mean bonus gap stood at 52.9%. |

| Keltbray, UK | 24.1% “official” mean gender pay gap - normalised to 25.73% when including those on furlough and making salary sacrifices |

Source: Company Gender Pay Gap reports